Madison Gambone, Contributing Member 2023-2024

Intellectual Property and Computer Law Journal

Introduction

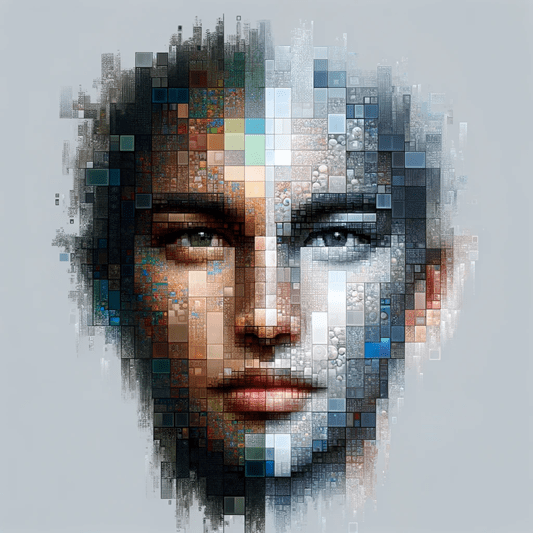

In the digital age, the boundaries between reality and technology are increasingly blurred, giving rise to novel legal and ethical challenges. One challenge is the intersection of Name, Image, and Likeness (“NIL”) rights and the rapid advancements in AI image creation services (“Image Generators”). In this blog post, the focus is on the profound impact of Image Generators that craft seemingly authentic images of individuals and how this intersects with the protection of one’s personal identity and brand.

As AI algorithms become increasingly proficient at generating lifelike images, the potential for infringement upon individuals’ NIL rights becomes more significant. Individuals, especially celebrities and public figures, have an interest in controlling the use of their name and likeness, not only for personal privacy but also for safeguarding their brand and reputation. Unfortunately, the average person does not escape the consequences as Image Generators blur the line between fiction and reality by producing seamlessly photoshopped images within seconds.[1] This blog aims to shed light on the challenges posed by Image Generators, examine the current legal landscape, and propose a legal framework to address this emerging issue.

Understanding NIL Rights and the Challenges Posed by Image Generators

NIL rights are a set of legal principles that grant individuals, especially celebrities and public figures, the authority to control the commercial use of their name, image, and other personal attributes.[2] These rights are paramount for safeguarding an individual’s personal identity, privacy, and reputation.[3] Since personal brands and images can be exploited for commercial gain, NIL rights play a pivotal role.[4] NIL rights empower individuals to determine how their name and likeness are used in advertisements, endorsements, merchandise, and other commercial ventures.[5] The significance of NIL rights extends beyond the realm of celebrity; they apply to anyone whose identity can be exploited for financial gain, reinforcing the idea that one’s name and image are not mere commodities to be exploited without consent.[6]

NIL rights originate from the right of publicity which protects unauthorized commercial exploitation of one’s persona.[7] The right of publicity is not recognized federally; it is governed by state law and varies by jurisdiction.[8] For example, California’s right of publicity statute covers the use of a person’s NIL in any manner whereas Ohio’s only covers if it has a commercial value, but excludes any noncommercial work or production, political or newsworthy material, or original works of fine art.[9] Ohio’s statute also carves out an exception for use of one’s persona in connection with any news, public affairs, sports broadcast, or account.[10]

Image Generators, in simple terms, take a text or image prompt, pull from their vast learned datasets, and produce new images that bear similarities in style and content to those in the training data.[11] Image Generators use artificial neural networks to create original and realistic images.[12] The artificial neural network is the combination of algorithms that learned different aspects and characteristics of images through training on extensive amounts of data.[13] Some popular Image Generators are DALL-E, Midjourney, and Stable Diffusion.[14]

The key challenges to addressing AI’s violation of NIL are the difficulty in identifying a source and overcoming the expressive work defense. Identifying the source of infringing content is difficult because AI technology is widely available.[15] It is also unclear if a user providing prompts or the Image Generator itself is the creator.[16] If the user innocently describes the name, image, or likeness of an individual, and the Image Generator produces an NIL infringement, is the user to blame? Since Image Generators use copies of protected works to produce transformative works that do not derive value from the celebrity’s fame, it is unlikely the Image Generator could be responsible.[17] Even if the creator is identified, social media allows fake images to be easily shared, making enforcement difficult because social media providers are immunized from liability for right of publicity claims arising out of user-generated content.[18]

Social media providers are not the only ones escaping liability for NIL infringements. The scattered case law and numerous defenses available make it difficult for anyone to enforce a right of publicity action.[19] The most difficult defense to overcome is the expressive works defense, which is based on the idea that the First Amendment protects all expressive works (except advertisements) against a right of publicity claim.[20] The case law varies between jurisdictions and is typically based on a broad, subjective test that requires the work to be transformative and disallows it if the value is primarily derived from the celebrity’s fame.[21] The inquiry depends on “whether the celebrity likeness is one of the ‘raw materials’ from which an original work is synthesized, or whether the depiction or imitation of the celebrity is the very sum and substance of the work in question.”[22]

The Current Legal Landscape Addressing Image Generators and NIL

A recent decision by the United States District Court for the Central District of California to deny NeoCortext’s motion to dismiss sheds light on the current legal landscape for NIL rights and Image Generators.[23] In Young v. Neocortext, Inc., Kyland Young, a cast member of the reality show Big Brother, filed a class action lawsuit against NeoCortext, Inc., the creator of the app Reface, for using his and other plaintiffs’ names and likeness to generate profits without consent.[24] Reface offers a free and subscription option that allows users to swap faces with actors, musicians, athletes, celebrities, and other well-known individuals in scenes from popular shows and movies.[25] To use Reface, a user chooses an individual from Reface’s searchable catalogue of images and videos of different celebrities compiled from a variety of websites, then uploads an image from their phone.[26] Reface then identifies the faces in the photographs and generates a new image, swapping the faces of the celebrity for the user.[27]

To establish a right of publicity claim in California, the plaintiff is required to establish: (1) defendant’s knowing use of the plaintiff’s identity; (2) the appropriation of plaintiff’s name or likeness to defendant’s advantage, commercially or otherwise; (3) a direct connection between the alleged use and the commercial purpose; (4) a lack of consent; and (5) a resulting injury.[28] NeoCortext argued that Young failed to establish the knowingly element. The Court rejected NeoCortext’s argument and found that using Young’s identity in a way that compiled his images with his name and made the images available for users to manipulate, was knowingly using his identity.

Additionally, NeoCortext argued the expressive works defense, claiming the generated image is transformative because Young’s image appears in a new work where his face does not appear.[29] The Court disagreed, finding the image was not so transformed that it reduced the “shock value” of the user’s face on Young’s body, and that “it may ultimately be deemed transformative as a matter of fact, that does not entitle NeoCortext to the defense as a matter of law.”[30]

Young v. Neocortext, Inc., though still being litigated, raises many questions about the current legal landscape for individuals looking to protect their NIL rights.[31] First, will other courts find that AI-generated images infringing on an individual’s likeness are not transformed enough to meet the expressive work defense? Is an Image Generator knowingly using one’s identity when it compiles data with an individual’s image and name and allows users to manipulate the image through a prompt? Finally, is a paid service that uses the ability to replicate an individual’s likeness in an advertisement enough to satisfy elements (3) and (4) of a right of publicity claim? The United States District Court for the Northern District of California does not think so.[32]

In Andersen v. Stability AI Ltd., the plaintiffs, three artists[33], filed a class action against Stable Diffusion, an AI software product, claiming Stable Diffusion was trained on plaintiffs’ works of art to be able to produce Output Images in the style of particular artists.[34] The Court granted defendants’ motions to dismiss but gave plaintiffs leave to amend.[35]

Plaintiffs asserted two right of publicity claims, alleging defendants: (1) knowingly used plaintiffs’ names in their products by allowing users to request art in the style of their names violating their right of publicity because their names are uniquely associated with their art and distinctive artistic styles; and (2) violated their rights in their artistic identities because the products allow users to request Output Images in the style of their artistic identities.[36]

Although the defense of expressive work will be decided based on the evidentiary record after plaintiffs amend their right of publicity claim, the Court stated “…plaintiffs’ current Complaint appears to admit that the DeviantArt’s Output Images are not likely to be substantially similar to plaintiff’s works captured as Training Images, and therefore may be the result of substantial transformation…”[37]

While the Court gave leave to amend, the plaintiffs would be required to: (1) show the defendants used their specific names to advertise or solicit purchases; (2) demonstrate how using their names resulted in an image similar enough that those familiar with their art style would reasonably believe plaintiffs created the image; and (3) result in plausible harm of their goodwill associated with their names.[38] The Court added that plaintiffs need to show this despite claiming none of the generated images are likely to be a close match to any of their work used in the Image Generator’s training.[39] All despite the fact that their copyright infringement claim includes an allegation that the images are not likely to be a close match to any of their actual work.

As demonstrated by the Court’s opinion, the plaintiffs are fighting an uphill battle. To succeed in protecting their NIL rights, plaintiffs would need to simultaneously prove that the generated images are similar enough to convince someone familiar with their style that they produced the work, while still asserting the images are distinct enough to harm their goodwill. Unfortunately, Andersen v. Stability AI Ltd., and Young v. Neocortext Inc., perfectly illustrate the difficulties in protecting one’s name and likeness in the current legal landscape.

Proposed Legal Framework

One solution to protecting NIL rights may lie in changing the Copyright Act to include language that enforces right of publicity claims. Currently, exploitation of one’s likeness, even if embodied in a photograph, is not protected by the Copyright Act.[40] For example, a photograph of a celebrity is a pictorial work of authorship providing copyright protection to the owner of such image, whereas the commercial use of the likeness of the individual depicted is not protected.[41] If NIL rights were incorporated into the Copyright Act, individuals could assert copyright infringement for use of their name, image, or likeness without risking different results across the states.

Another solution would be the adoption of strict legislation that defines the expressive works exception. A federal definition ensures individuals are not better protected in one state over another, gives clarity to those whose NIL rights are violated, and sets guidelines for the potential violators. A stricter definition might include language defining transformative as so transformative that a reasonable person familiar with the work would view it as no more than an inspiration, less than substantial, and never as a derivative. Additionally, the language could emphasize that a work can never intend or seem to intend to imitate one or several individuals whose consent has not been given. Finally, the language could clearly set parameters for Image Generators’ ability to create works that are or can be used for commercial purposes without consent.

Conclusion

In conclusion, as AI technology continues to evolve, the legal frameworks governing NIL rights must also adapt. The challenges posed by Image Generators, as seen in cases like Young v. Neocortext, Inc. and Andersen v. Stability AI Ltd., highlight the need for a more cohesive approach to NIL rights.

Incorporating NIL rights into the Copyright Act could provide a more unified and enforceable standard across states, offering greater protection for individuals against unauthorized use of their likeness. Additionally, a more precise definition of the expressive works exception at the federal level would help clarify the boundaries between creative freedom and NIL rights infringement, ensuring fair use without compromising individual privacy and reputation.

Ultimately, the goal should be to strike a balance that respects the right of individuals to control their own images and identities, while also allowing for innovation and creativity in the world of growing AI. It is crucial for lawmakers, tech companies, and the public to be conscious of NIL rights and to ensure these rights are protected in a fair way that is adaptable to future technological advancements.

[1] I tried describing myself to an Image Generator (dezgo.com) and was shocked at how similar and realistic the image was.

[2] Ai wants your nil – especially if you’re a celebrity Lexology, (last visited Nov 2, 2023) https://www.lexology.com/commentary/intellectual-property/usa/venable-llp/ai-wants-your-nil-especially-if-youre-a-celebrity [herein after lexology].

[3] Id.

[4] Id.

[5] Id.

[6] Id.

[7] Id.

[8] Id.

[9] Id.; Ohio Rev. Code Ann. §§ 2741.02, 2741.09.

[10] Id. at §§ 2741.02, 2741.09.

[11] Ai image generation, explained. AltexSoft, (last visited Nov 2, 2023) https://www.altexsoft.com/blog/ai-image-generation/.

[12] Id.

[13] Id.

[14] Id.

[15] lexology, supra note 2.

[16] Id.

[17] Andersen v. Stability AI Ltd., 23-cv-00201-WHO at *3 (N.D. Cal. Oct. 30, 2023).

[18] 47 U.S.C.S. § 230.

[19] Can The Law Prevent AI From Duplicating Actors? It’s Complicated Forbes, (last visited Nov 2, 2023) https://www.forbes.com/sites/schuylermoore/2023/07/13/protecting-celebrities-including-all-actors-from-ai-with-the-right-of-publicity/?sh=62f07ca559ec.

[20] Id.

[21] Young v. Neocortext, Inc., No. 2:23-cv-02496-WLH(PVCx), 2023 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 171050, at *18 (C.D. Cal. Sep. 5, 2023).

[22] Id. at 18-19.

[23] Id. at 1-2.

[24] Id. at 4.

[25] Id. at 2.

[26] Id.

[27] Id.

[28] Id. at 21.

[29] Id. at 19.

[30] Id. at 21.

[31] While the case does not explicitly state that Reface is an Image Generator, it functions in a similar way. The app takes an image prompt (the image supplied by the user), pulls from its learned datasets (the learned algorithm of identifying faces and pulling from the actual dataset of celebrity photos), and produces a new image that bears similarities in style and content to those in the training data.

[32] Andersen, 23-cv-00201-WHO.

[33] The artists/ plaintiffs are Sarah Anderson, Kelly McKernan, and Karla Ortiz.

[34] Id. at 2.

[35] Id. at 3.

[36] Id. at 33-34.

[37] Id. at 38.

[38] Id. at 35-36.

[39] Id. at 36.

[40] Young, No. 2:23-cv-02496-WLH(PVCx), at 14.

[41] Id. at 14.

Leave a comment