Jackson Weist, Contributing Member 2024-2025

Intellectual Property and Computer Law Journal

I. Introduction

In 2022, the global market for guitars alone was valued at over $10 billion.[1] Compare this to the piano industry, which in 2023 had a market size of only $2.36 million.[2] With such a tremendous market for just one instrument, industry members seek a wide variety of intellectual property protections for their works. However, for an instrument dating back to the 1600s, the genericness and lack of originality of designs may pose eligibility issues for intellectual property protection. Currently, two manufacturers – Gibson and Dean Guitars – are embroiled in a trademark infringement case where the result could change the landscape for guitar manufacturers across the world.

This article explores the history and current state of ongoing litigation regarding Gibson’s trademarks over their iconic guitar body shapes. Part II provides background on the history of Gibson as a company and their trademarks, as well as Dean Guitars, the company allegedly violating Gibson’s trademarks. Part III explores the current litigation: from the original 2019 case and decision, through the 2024 appeal and order for retrial. Part IV concludes by considering what the new trial’s result could mean for guitar manufacturers across the world.

II. Background

History of Gibson Guitars

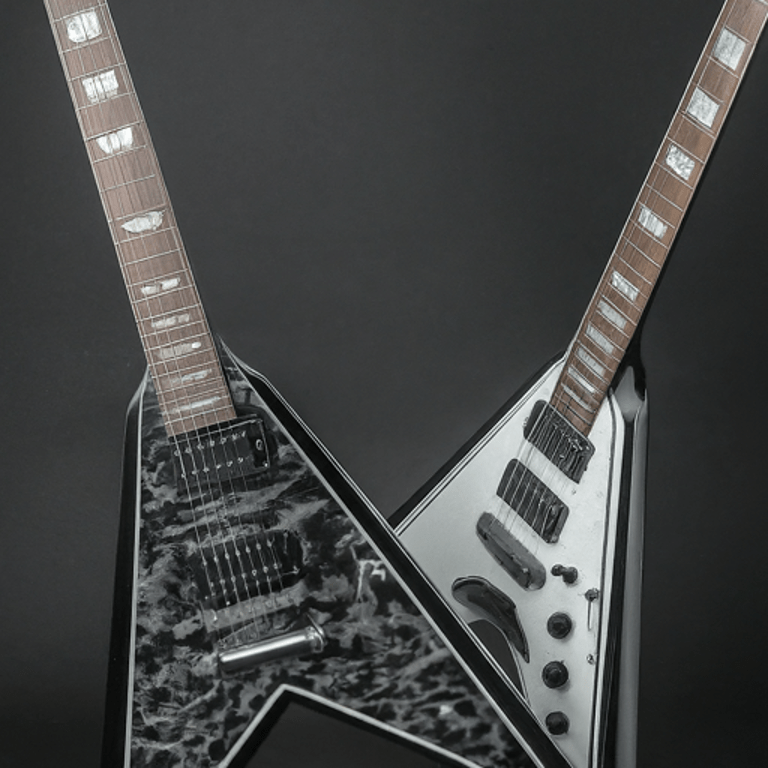

Gibson was established in 1894, originally in Kalamazoo, Michigan and then soon moved to Nashville, Tennessee.[3] Gibson began by producing acoustic guitars and mandolins, until the 1940s when they began producing electric guitars.[4] In the 1950s they released two guitars: the “Explorer,” featuring a zig-zag body shape resembling the letter Z, and the “Flying V,” featuring an angular body shape resembling the letter V.[5] Both guitars would become hugely popular for their distinct body shapes, with several famous guitarists of the time becoming well known for their use of the two guitars.[6] Gibson’s success prompted them creating more guitars with distinct body shapes, including the “Standard Guitar,” known colloquially as the SG, and the “ES-335.”[7] In 1960, Gibson received both patents and trademarks for all these guitar body shapes as well as the dove wing headstock featured on many of their guitars. They also received a trademark for the “Hummingbird” word mark used on a line of their acoustic guitars.[8]

Gibson has a history of using the legal system to protect their designs. In the 1970s they won a legal battle against other guitar manufacturing giant Ibanez over Ibanez’ use of wing-shaped headstocks.[9] However, as the guitar industry has developed and their once-iconic designs have become more commonly used, Gibson is becoming less successful in defending their designs. In 2018 they were denied their trademark application for the “Flying V” in the European Union as the court decided the design, while unique upon its release, was now “too commonplace for protection.” [10]

History of the Dean Brand

Dean was established in 1976 in Evanston, Illinois, and quickly released two of their own models of guitar: the Dean Z and Dean V.[11] These guitars featured similar shapes to the “Explorer” and “Flying V” respectively, and also grew to become very popular among musicians.[12] Dean was sold in 1991 to Tropical Music Export Enterprises who continued to manufacture guitars similar to the Dean Z and Dean V.[13] In 1995, the company Armadillo purchased the Dean brand from Tropical Music, and they would continue manufacturing guitars similar to the Dean Z and Dean V with a wing-shaped headstock and the Dean brand mark.[14] In 2010, Armadillo released a new line of acoustic guitars under the Dean brand called Luna Athena, one of which had a body shaped similarly to the Gibson ES-335, and another was an acoustic titled the “Hummingbird.”[15] The same year, Armadillo released another guitar under the Dean brand called the “Gran Sport” which had a body shape similar to that of Gibson’s SGs.[16]

Legal Battles Between the Two Companies

Despite the similarities in their guitar body designs, legal disputes between the two companies only began in 2004 when Armadillo’s holding company Concordia filed for a trademark for a wing-shaped headstock.[17] Gibson moved to prevent this registration because of the concern that it would be confused with their own dove wing headstock.[18] The two companies attempted to resolve this outside of court, with Armadillo wanting a license to the headstock shape as well as the guitar body shapes.[19] They went as far as having a fully-drafted agreement, however, the deal was never finalized and the Trademark Trial and Appeal Board eventually denied Armadillo’s application in 2009, stating that the Dean headstock was likely to cause confusion with Gibson’s.[20] Gibson faced financial woes in the late 2010s, emerging from Chapter 11 bankruptcy in November 2018. Their new executive leadership were unhappy with Armadillo’s continued use of similar guitar body shapes.[21]

III. Discussion

Gibson’s Claims

In 2019, Gibson filed suit against Armadillo and Concordia alleging that they had willfully infringed Gibson’s trademarked body shapes of the Explorer, Flying V, SG, ES-335, and the wing-shaped headstock.[22] They also alleged that Armadillo had infringed upon the word mark for the “Hummingbird,” and that Armadillo was willfully selling counterfeits of Gibson products.[23]

Trademark Law

To fully understand Gibson’s claims, it is important to understand the basis of United States trademark law. In the US, trademarks protect the commercial use of designs, words, names, or symbols which serve to distinguish where a good comes from.[24] There are two elements which determine trademark eligibility: first, the mark must be used in commerce, and second, the mark needs to be “distinctive.”[25] There is no question that Gibson’s guitar bodies are used for commerce, as Gibson has been selling these guitars for 70 years. However, the distinctiveness element may be called into question for their “genericness.” A mark which is too generic is not considered “distinct” enough for trademark protection, and a mark which originally received a trademark because it was distinct can over time become generic and lose its trademark protection.[26]

Doctrine of Laches

In addition to a mark losing trademark protections over time because it becomes generic, a trademark holder may lose their trademark if they do not enforce it.[27] The doctrine of laches is a concept whereby a trademark loses its enforceability if a company does not assert its ownership of the trademark in a reasonable time.[28] For example, if a trademark holder allowed a competitor to use nearly identical guitar bodies for nearly 50 years without defending this misuse in court, then the trademark holder might lose their trademark ownership.

Armadillo’s Defenses

Armadillo had six main defenses: 1) that Gibson’s claims were barred by the doctrine of laches; 2) that Gibson’s marks were too generic for trademark protection; 3) that Armadillo’s guitars were always sold with the Dean branding marks; 4) that Gibson failed to create a genuine dispute of material fact as to if consumers were actually confused between their products; 5) that consumers were familiar with differentiating guitar brands from each other; and 6) that Gibson’s counterfeiting claims must fail as a matter of law due to Armadillo using its own branding marks on their guitars.[29]

Excluded Evidence

To aid their argument regarding the genericness of Gibson’s designs, Armadillo attempted to include evidence of third-party use of these body shapes dating back decades.[30] However, the district court barred the admission of any evidence to third-party use prior to 1992 – five years before Armadillo acquired the Dean brand.[31] Gibson argued that any evidence allowed prior to 1992 would be hearsay and marginally relevant as it was too distant from Armadillo and Concordia’s purchase of Dean.[32] The district court relied on the case Converse, Inc v. International Trade Commission, stating that evidence of third-party use “older than five years should only be considered relevant if there is evidence that such uses were likely to have impacted consumers’ perceptions of the mark as of the relevant date.”[33]

District Court’s Ruling

The district court ruled in Gibson’s favor that Armadillo had violated the trademarks for all the guitar bodies, as well as held that Armadillo had been issuing counterfeits of these models.[34] While Gibson received only $4,000 in damages, the most significant impact was that Armadillo was enjoined from continuing production of the infringing models – products which they had been selling and building their business upon for decades.[35] Armadillo was also held in contempt of court in 2023 for continuing to list these models on their website. Despite this, the Dean Z and Dean V are proudly presented on the front page of Dean’s website next to the caption “ZERO F*CKS [sic] GIVEN.” [36][37]

Appeal and Order for Retrial

Armadillo appealed the ruling, and in July 2024 the Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals ordered a re-trial of the case to allow new evidence to be presented in favor of Armadillo.[38] The Fifth Circuit reasoned that the district court had misinterpreted Converse, stating that the context of that case indicates that the five-year time period is not a hardline rule, and the district court should have allowed Armadillo to argue why that evidence might have been relevant to the case before deciding if it should be admitted.[39] Because of this abuse of discretion, the Fifth Circuit concluded that the barred evidence of third-party use could have been hugely important to Armadillo advancing their case and therefore remanded the district court’s ruling with instructions to retrial.

IV. Conclusion

The result of this new trial could have a far-reaching impact on the guitar manufacturing world. If Armadillo can use this new evidence to convince the jury that Gibson’s marks are too generic for protection, these designs will be open for any manufacturer. Gibson would, however, still hold their patents for these designs, meaning manufacturers would still have to make their own versions of the guitar body instead of wholesale taking the Gibson design’s specifications. That being said, if Gibson loses these trademarks, it could create a new world for the guitar manufacturing industry, wherein several historied body shapes are no longer tied to just one brand, but open for use by anyone.

[1] Guitar Market Size, Share & Trends Analysis Report By Product (Acoustic And Electric), By Distribution Channel (Offline And Online), By Region, And Segment Forecasts, 2022 – 2030, Grand View Research, https://www.grandviewresearch.com/industry-analysis/guitar-marketreport#:~:text=Report%20Overview,7.7%25%20from%202023%20to%202030 [https://perma.cc/3YNY-HKHU].

[2] Global Piano Market Size By Type of Piano, By Target Demographics, By Technology, By Geographic Scope and Forecast, Verified Market Research (May, 2024), https://www.verifiedmarketresearch.com/product/piano-market/#:~:text=Piano%20Market%20was%20valued%20at,the%20 forecast%20period%202024%2D2030 [https://perma.cc/28R5-GYPR].

[3] Gibson, Inc. v. Armadillo Distrib. Ents., 107 F.4th 444 (5th Cir. 2024).

[4] Id.

[5] Id.

[6] Id.

[7] Id.

[8] Id.

[9] Elyadeen Anbar, The True Story Behind Japanese ‘Lawsuit’ Guitars, Flypaper (Feb. 8, 2017), https://flypaper.soundfly.com/discover/truth-lawsuit-era-guitars/#:~:text=Speaking%20of%20which%2C%20in%201977,the%20second%20design [https://perma.cc/K7RW-Q8S5].

[10] Josh Gardner, Gibson Loses Flying V Trademark Case in EU Court, Guitar.com (June 28, 2019), https://guitar.com/news/gibson-loses-flying-v-trademark-case-in-eu-court/ [https://perma.cc/28DF-PKTS].

[11] 107 F.4th 444 (5th Cir. 2024).

[12] Id.

[13] Id.

[14] Id.

[15] Id.

[16] Id.

[17] Id.

[18] Id.

[19] Id.

[20] Id.

[21] Id. at 445.

[22] Id.

[23] Id.

[24] 15 U.S.C § 1127

[25] Id.

[26] Id.

[27] Legal Information Institute, Laches (June 2023), https://www.law.cornell.edu/wex/laches [https://perma.cc/8VRF-BYEU].

[28] Id.

[29] 107 F.4th 445 (5th Cir. 2024).

[30] Id.

[31] Id.

[32] Id.

[33] Id at 446.

[34] Id.

[35] Gibson Brands, Inc. v. Armadillo Distrib. Enter., E.D.Tex. Civil Action No. 4:19-cv-00358, 2023 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 35905 (Mar. 3, 2023).

[36] Id.

[37] Dean Guitars, https://www.deanguitars.com/ (last visited Sept. 13, 2024).

[38] 107 F.4th 451 (5th Cir. 2024).

[39] Id.2.

Leave a comment